Way back in February 2020 B.C. (Before Covid), U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Commissioner Hester Peirce put together a proposal to help the blockchain industry innovate in a safe manner. In plain language, she suggested a three-year “Safe Harbor” — or grace period — to allow blockchain projects to achieve decentralization, allowing more projects to be “born in the USA.”

We were very supportive of this idea, and since Commissioner Peirce asked for feedback from the blockchain community, we worked with our Bitcoin Market Journal newsletter subscribers to help improve the proposal. (Many of you are credited on the title page.)

Recently, Commissioner Peirce issued Safe Harbor 2.0, an updated version of her proposal, and we were pleased to see that many of your ideas and suggestions made it into the new document, which was released on GitHub (that’s just cool).

In this article I will simply describe the problem that we’re trying to solve, and why Safe Harbor 2.0 is a huge step forward, protecting both investors and the blockchain industry. I’ll try to also paint a picture of what things might look like if this becomes law, so you can decide whether to support it.

The Problem We’re Trying to Solve

Flash back to the blockchain boom of 2017-2018, when new projects were being launched every day using initial coin offerings (ICOs). These were heady times, with blockchain startups looking to raise millions of dollars from investors. In a typical ICO, blockchain investors would buy tokens (similar to buying shares of a startup company), then hope the tokens would go up in price so they could sell them for a profit.

This caused an explosion of new blockchain projects, as both founders and investors saw an opportunity to make “easy money.” Most of these projects (like most startups) never went anywhere, so many of these tokens became worthless.

For the SEC, whose charge is to protect investors, the central question is this: is a blockchain token an unregistered security? Investors were acting like they were buying stock in a high-flying tech company. But were they?

Put another way, are the stock market and the block market two different things?

This question had huge implications. If tokens were like stocks, then blockchain investors were really buying unregistered securities, which is illegal. In many ways, they sure looked like stock offerings, as defined by the famous Howey Test (explained here using adorable cat photos).

But there is a case to be made that “stocks” and “blocks” were different. As Commissioner Peirce pointed out, a decentralized blockchain network like Ethereum doesn’t look like a public company. There’s no CEO, no earnings statements, no legal entity. It’s more like a … well, like a network.

However, someone has to create a decentralized network in the first place: it has to start somewhere. Imagine if Vitalik Buterin started building Ethereum, and the government stepped in as soon as someone bought the first ETH, calling it an “unregistered security!” and hauling him off to prison.

This is the Catch-22. When blockchain projects become decentralized, they are no longer like a company — but if they don’t start off like a company, they can’t become decentralized. Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?

Commissioner Peirce’s proposal neatly solves this problem by giving new blockchain projects a three-year grace period, during which they can develop the code and build the community, with the goal of becoming decentralized. At the end of three years, they can either show that their project is decentralized, or register their tokens as securities (like traditional stocks).

The idea sounds great, but the devil is in the details. Let’s look at how the Safe Harbor 2.0 proposal evolves this basic concept – how it gives entrepreneurs three years to hatch the egg into a chicken.

Safe Harbor 2.0: How It Might Work

I’ll outline the major benefits as I see them, showing how a future Buterin could launch a blockchain project while still protecting investors. Note this is my interpretation of Commissioner Peirce’s document (not an official statement), but with the benefit of having lived through the ICO craze.

If you are creating and launching a new blockchain project, then under the Proposed Safe Harbor 2.0:

- The goal of your project will be decentralization. In other words, you’re not using tokens to fund your traditional startup, then slapping “blockchain” in front of the name. Investors may not know how it will turn out, but they know what they’re getting into.

- You will clearly disclose your development team. This is a huge step forward from the 2018 boom, where it was not uncommon to see “anonymous founders.” Here investors have transparency and accountability — they know who’s behind the project.

- Everything will be open source. Investors will be able to examine the source code, which can help prevent both scams (intentional) and hacks (accidental). Operating in broad daylight also provides rigor and transparency for blockchain teams.

- You will have a block explorer. This is an incredibly good idea, so investors can see all the transactions made on the blockchain. Public companies don’t have this. The stock market doesn’t have this. It will be a huge step forward in financial transparency.

- You will clearly describe the “tokenomics.” This is another huge step forward: investors must understand the launch and supply, how many tokens were pre-sold (and to whom), how new tokens are minted or mined, and how the rules might be changed in the future.

- You will clearly lay out a development plan. Investors will have a roadmap for achieving decentralization, with target milestones and quantifiable metrics (i.e., numbers) so investors will be able to measure whether those milestones are being achieved.

- You will provide a warning to token purchasers. You must explain there’s a high degree of risk, most startups fail, and that investors should only put in as much as they’re willing to lose.

- You will give six-month updates on all the above. This lets investors see what you’ve achieved, and it provides accountability to your project team to keep moving.

- You will file your intent with the SEC. This alone sets a “bar of entry” that weeds out a lot of weaker projects, while also creating a handy watchlist for the SEC. In return for this “entry fee,” entrepreneurs will get a three-year grace period.

- You will file an “Exit Report” at the end of three years, showing whether decentralization has been achieved. (More on this below.)

In summary, Safe Harbor 2.0 is a meaningful step forward for both investors and the industry. Commissioner Peirce gets it.

But there’s still one more problem. You might say it’s the central problem.

How to Define Decentralization

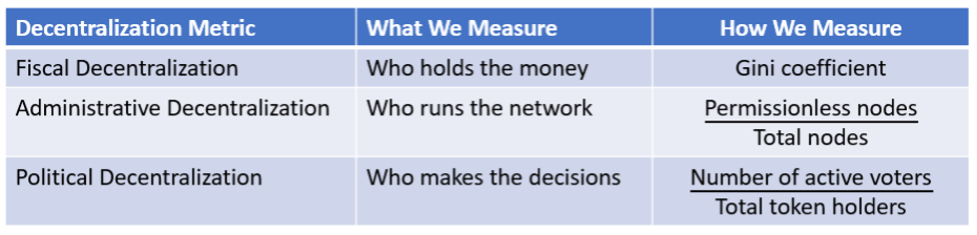

This is perhaps the thorniest issue that we faced when writing our response to the original proposal. After much debate, we ended up suggesting three “Tests of Decentralization” (see page 11) in the form of mathematical formulas, but these received a fair amount of criticism.

The key question is: can decentralization be measured?

Commissioner Peirce’s new proposal suggests that at the end of three years, blockchain teams hire an outside lawyer to argue whether their project has met the “tests of decentralization,” which she describes as (my words):

- The blockchain network is not likely to be controlled by any one person or group, OR

- The token behaves functionally more like a “utility token”

This is a critical issue that we still need to resolve. If decentralization is quantifiable (i.e., if we can measure it using hard numbers), then we have a simple test — although it leads to blockchain teams trying to game the system so they meet the numbers.

On the other hand, if decentralization is more a “legal argument” that meets one of the two criteria above, then we have a lot of lawyers (and bureaucrats) arguing whether it is or is not decentralized at the end of three years — a precarious grey area.

Even if this becomes law tomorrow, it could be we still have three years to figure this out. As we’ve seen in the last three years, this industry evolves at breakneck speed. But let’s get started now, with more thoughtful debate around this key issue: how do we define decentralization?

The central issue, it seems to me, is decentralization. I welcome your feedback.

John Hargrave is the author of Blockchain for Everyone: How I Learned the Secrets of the New Millionaire Class, the bible of blockchain investing.