Here’s the announcement of the new blockchain education program with the Massachusetts state government. It’s a big deal.

We have a vision for where this kind of partnership can go, when governments begin educating themselves on the power of bitcoin and blockchain. That vision can be summed up in two words: Kendall Square.

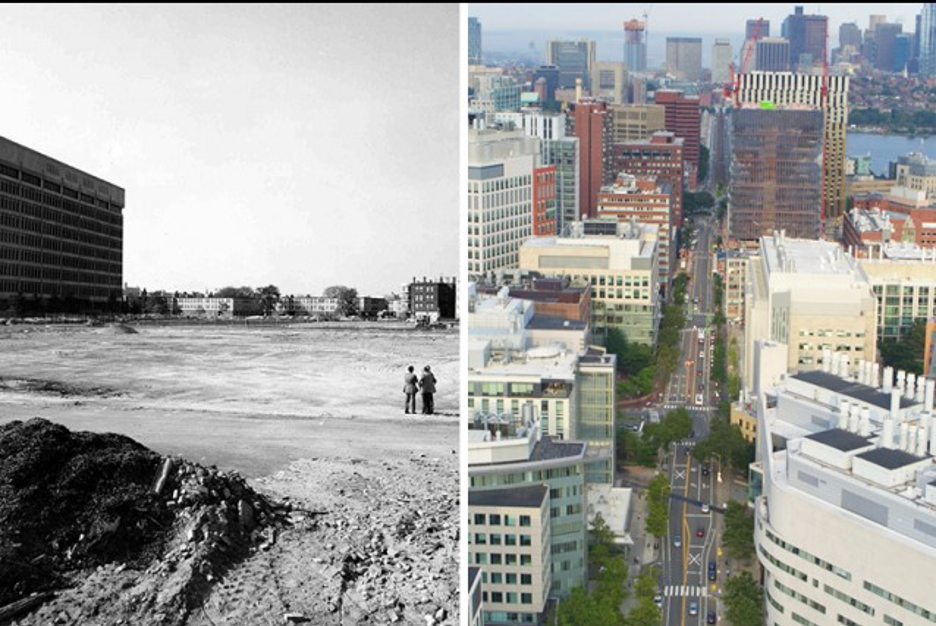

The Kendall Square neighborhood lies next to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, stretching along the Charles River that separates Cambridge from Boston. (Here’s a map.) Although you’d think this would be valuable real estate, a series of unfortunate events led this area into decay and decline from the 1970s through the 1990s. Residents avoided the area after dark.

I remember it vividly, because I got my first job there.

When I stepped off the Kendall Square subway line for my job interview as a fresh-faced college student, it was a concrete wasteland. I walked through empty parking lots, the wind whipping whirling dervishes of dust around me. The area felt so desolate and lonely that I expected to see a tumbleweed roll by.

The job, it turned out, was a weird one. Located within one of those crumbling brick buildings in Kendall Square was a company that specialized in telephone-based chat rooms, and they needed college students to serve as operators.

Before the Internet, a phone-based chat room – also known as a “party line” – was a kind of special number that you could call to chat with other strangers. Unlike 1-800 toll-free numbers, “1-900 numbers” were “toll-full,” with a per-minute fee to call in (“20 cents for the first minute, 10 cents for every other minute,” as we had to remind callers several times an hour). Based on what the operators got paid, it must have been a a wildly profitable business.

This line was marketed to teens, so huge numbers of bored teenagers would call in just to chat with other teenagers. The conversation was usually innocuous – in fact, we had strict orders to disconnect anyone using inappropriate language – but some kids would really get hooked on the service, spending weeks on the chat line. Then their parents would get the phone bill, and we’d never hear from them again.

As an operator, I sat behind an enormous digital switchboard, with little LEDs representing each person connected to the chat line. Friday and Saturday nights were crazy, with easily a hundred callers at a time. They were grouped into chat rooms of 10 callers each, and I had godlike powers to disconnect troublemakers, or speak with them one-on-one in a private room.

As college jobs go, it was a pretty good one. I often worked the overnight shift, which paid $1.00 more per hour. It was totally unsupervised, although they hired auditors to occasionally listen in and make sure you hadn’t fallen asleep on the job. (Apparently this was a problem.)

I had a window view of the vacant lots of Kendall Square, and I would stare out at the lonely streetlights as I listened to teenagers talk about Dawson’s Creek, or discuss how awesome they were at doing skateboard tricks. There was another company that ran 1-900 sex lines out of the office down the hall, so occasionally I would hear them through the thin walls. Their job sounded a lot more exciting.

It was a good college job, there in the wasteland of Kendall Square, and I left with my virtue intact. At sunrise, I would clock out, walking back through the asphalt jungle to my dorm room. If a traveler from the future had dropped in and said to me, “In 25 years, this will be the life sciences hub of the world! Genetic engineering! Drug development! Fabulous technology companies!”, then I would have had only one question.

How?

How to Build an Innovation Economy

The story of how Kendall Square went from dystopia to dream world is chronicled in the documentary From Controversy to Cure: Inside the Cambridge Biotech Boom. Long story short: it took a lot of commitment from government – and that commitment started with communication.

The education started at the local level, in Cambridge City Council meetings during the 1970s about the ethics of genetic engineering. Cambridge was seeing MIT researchers and startup companies exploring new frontiers in molecular biology, and a small group of residents became concerned. The city eventually took it upon themselves to regulate this growing industry.

Far from scaring off new biotech firms, that regulation began to welcome this new industry: not only did citizens and government leaders better accept and understand the science, but Cambridge became more attractive for biotech firms to set up their headquarters, since the city had a clear regulatory framework.

(Similarly, today’s blockchain industry is a confusing mishmash of conflicting regulations. The city or country that first develops this kind of regulatory framework will win.)

Thus, city-level government played a big role in rolling out the red carpet that transformed Kendall Square. But so did state-level government: in 2008, Gov. Deval Patrick rolled out a 10-year, $1 billion life sciences plan. It offered tax incentives for startups and established firms. It awarded grants for projects to treat blood diseases, bone grafts, and kidney failure. It made life sciences a “thing.”

Lured by the incentives, not to mention easy access to fresh talent from MIT and Harvard, biotech companies flocked to Kendall Square, which was transformed from a desert of parking lots into an oasis of sleek glass office buildings.

Governor Patrick’s 2008 plan was followed by an additional $500 million from his successor, Governor Charlie Baker, to keep the pipeline of jobs and innovation flowing. Now with the race for a COVID-19 vaccine in full-on sprint mode, Kendall Square-based companies like Moderna may become ground zero for the cure.

Kendall Square is now a leading example of the “innovation economy,” not a zero-sum game of producers and consumers, but a rapidly expanding pie based on continual innovation. And Cambridge is not the only U.S. city: Raleigh-Durham, NC has developed its Research Triangle; Madison, WI has become a hub for tech entrepreneurship; and cities like Denver, Salt Lake City, and Charleston are all growing an innovation economy.

What it takes, however, is government commitment. And commitment starts with communication. Which leads us to the big announcement.

How to Build an Innovation Economy

As you can read in the press release, our company Media Shower has partnered with the Innovation Institute at Massachusetts Technology Collaborative to create a Blockchain Education for Government Innovators series.

In plain language, this means we’re meeting with people on the leading edge of Massachusetts government – the same type of forward-thinkers who built the innovation economy of Kendall Square – to discuss how blockchain might offer the next leap forward.

It’s something like those early Cambridge City Council meetings, where everyone got educated on this new field called biotechnology. That understanding allowed a thousand flowers to bloom, digging up those concrete parking lots and planting a thriving biotech hub. It brought life sciences to life.

The need to educate our government leaders about blockchain has never been greater. The coming changes to the global economy will require governments to find new ways of creating and managing money, and blockchain technology offers future-thinking governments a way to think about the future.

It is easy, in these times, to fall into cynicism about the state of our government, to think that no one decent or honest is left in the system. Our experience has been the opposite: we have been encouraged by the smart, thoughtful people working with us in this blockchain education series. They understand a good deal about bitcoin and blockchain, and they’re eager to learn more.

Working with the government, has actually restored my faith in government. That’s good news. And next time you’re in Cambridge, take a walk through Kendall Square. It’s living proof that good government can make a difference.